By Malcolm Ryder

This current show born of the East Bay Photo Collective, which runs through September 3rd, is unusual for the gallery, but maybe not unusual as a sign of the times.

More specifically the brainchild of photographer/curator Jessica Chen, the vast majority of the works on display in The Stories We Tell are not for sale at the gallery. Instead, they hold tightly to the walls provided, for a public exposure of “private” matters – gently transposed, but still guarded, into “personal” information for social consideration. It is a calculated risk taken for cultivating diversity, equity, and inclusion.

I went to the show not knowing any of the artists and none of their works. That meant the rude but innocent question, “Why should I care?”, was floating in my mind when I arrived. Take that as an invitation rather than a challenge, however, and the show gives a strong answer. The goal of the show, clearly stated in its posters and postcards, is to explore stories as the pathway from one’s identity to one’s origins.

In this show, the mix of text, audio and photography is very much dominated by the varieties of storytelling through pictures. The multimedia sets are not forced at all, and we are free to only look at the pictures without their complementary written or recorded narratives. But each artist in the show provided a printed text giving clarity to how they understood photography to be a part of their storytelling.

The main effort in each artist’s presentation was, as billed, to describe their identity in terms of who they have belonged to or belonged with – the characters in their stories. Here we are talking about families, not just friends. Parents and the parents’ families; siblings in one’s own family; and of course images of one’s past self. Those characters shaped who the artist is today, but the artist now shapes the presence of those characters in the way the story is intended to make sense.

When I finished my visit, I had clarity about why one should see the show. Its influence is to inspire the viewer to find and tell their own story and to accept the past as something still alive in the social and emotional present.

Photographers have the responsibility to go beyond selecting an image because it has meaning. The real responsibility is to give the image meaning through its presentation. In that sense, every picture in the show is a special part of a group, where the whole set of them is greater than the sum of its parts. The show in its entirety is online and can be appreciated that way. My following notes are instead about how the pictures in their groupings are working, independently of text or audio, to tell the story in one way or another. But then, that adds up to their telling different kinds of stories.

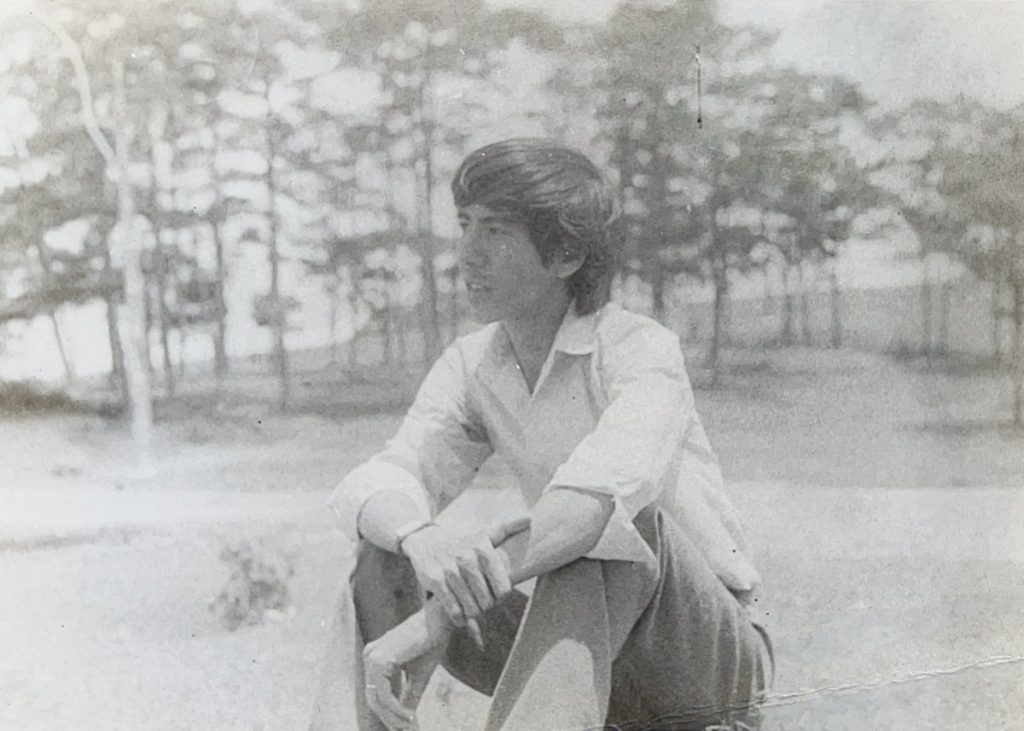

Ngân Vũ shows one image of a gravestone holding a memorial photo of the male deceased. This decisive point in time, the burial, seems to radiate outward into a mix of other portraits, some of them informally distant but direct like old-school family album snapshots, and others quite different and cinematic closeups. The distant shots seem to represent the past, and the closeups feel very much like the present day. We wonder if that also represents an evolution of photography’s way of working with the private space of intimacy.

Stella Kalaw gave a painterly celebration of a quiet domestic aesthetic, of rooms built all about selectivity and orderliness. The color in the pictures, both individually and across the whole group, is frankly emotional even though predominantly just a couple of warm toned large walls in green or amber. The uniformity of that image background eventually makes the tight clusters of other objects and colors in the room pop like sophisticated jewelry adorning elegant clothing of fine fabric. The spare, ultra-organized interiors take on an ambience of high-design, and the collection of them adds up to a sense of touring the home. Individually, some of the rooms feature, almost like afterthoughts, a framed picture mounted high on a main wall, showing persons whose role could be a god, muse, or descendant. Overall, the set deliberately projects a personality, presumably that of one of the people shown in the only photo aimed at presenting the inhabitants.

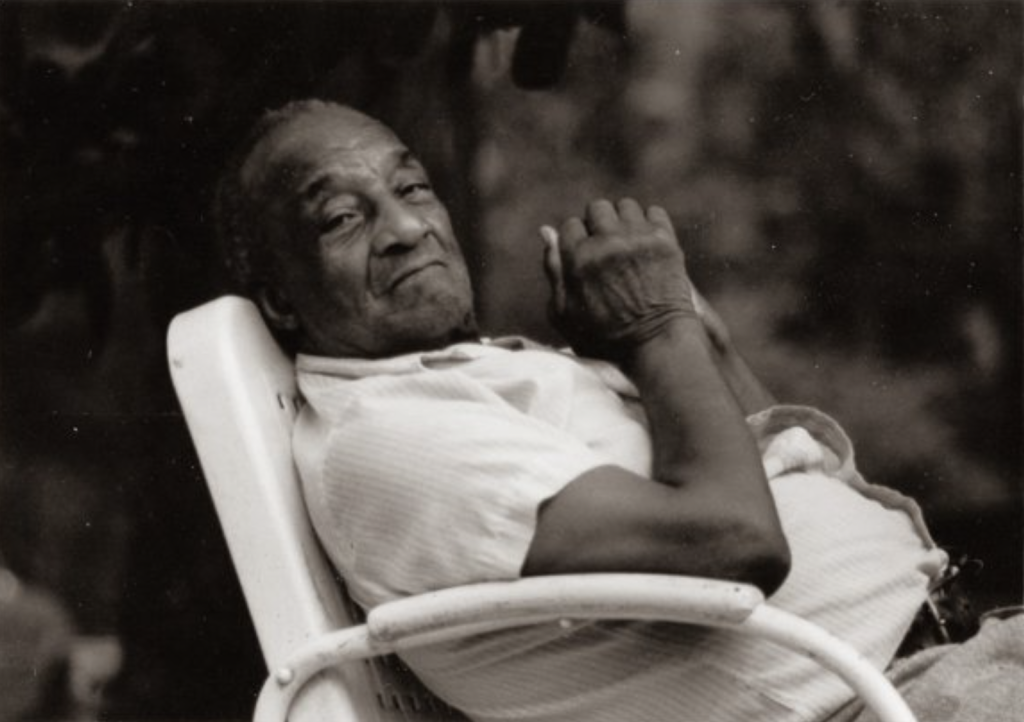

Gene Dominique casts his group of photos as a “family archive” – which is of course about preservation. This family’s curated archive highlights moments of satisfied achievement, self-conscious but relaxed. The shots on display speak as evidence, for a desirable history, but with an unforced matter-of-factness that doesn’t spark any need to dispute its truthfulness. Cast against the Jim Crow era, it is a forthright celebration of success, if not victory.

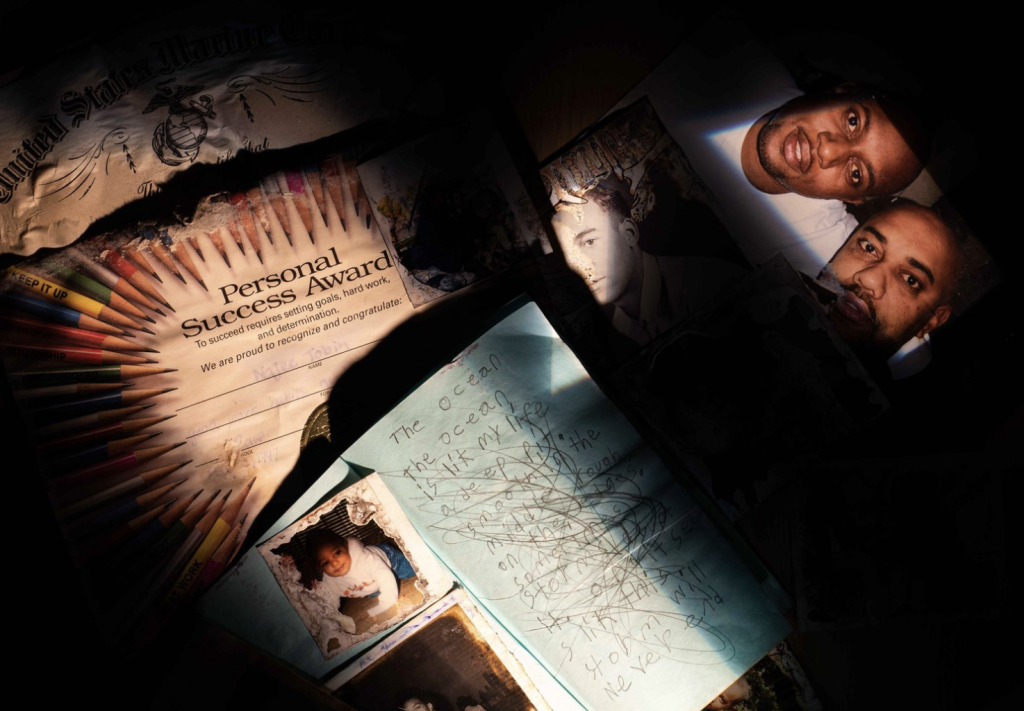

Najee Tobin pulls us into a very close inspection of his images, as if we were rummaging through drawers or shelves with him. The immediately interesting feature of his work is that with many of the photos, each one is itself a composed collection of certain memorabilia; then collectively the photos bind together as a new set of items in the same archive they study, like two mirrors infinitely, timelessly, reflecting each other. The titles of the respective pictures are succinctly different, and Tobin makes it clear in his statement that the pictures are about his perspective on the Black men around him. But overall, the set emanates the blending of parental pride and love that underlies achievement by their children.

Jessica Chen has a display that easily anchors the intent of the show to reflect sources of one’s identity. On her wall, two large shadow boxes are vaults for documentary group (family) portraits, in which there is no telling of who later became what, but each person is given equal importance. Those boxes are flanked left and right by a somewhat journalistic composite portrait of her father, in which each individual image emphasizes liveliness, and which all together make us feel in the end like we have spent time with him, or have met him ourselves.

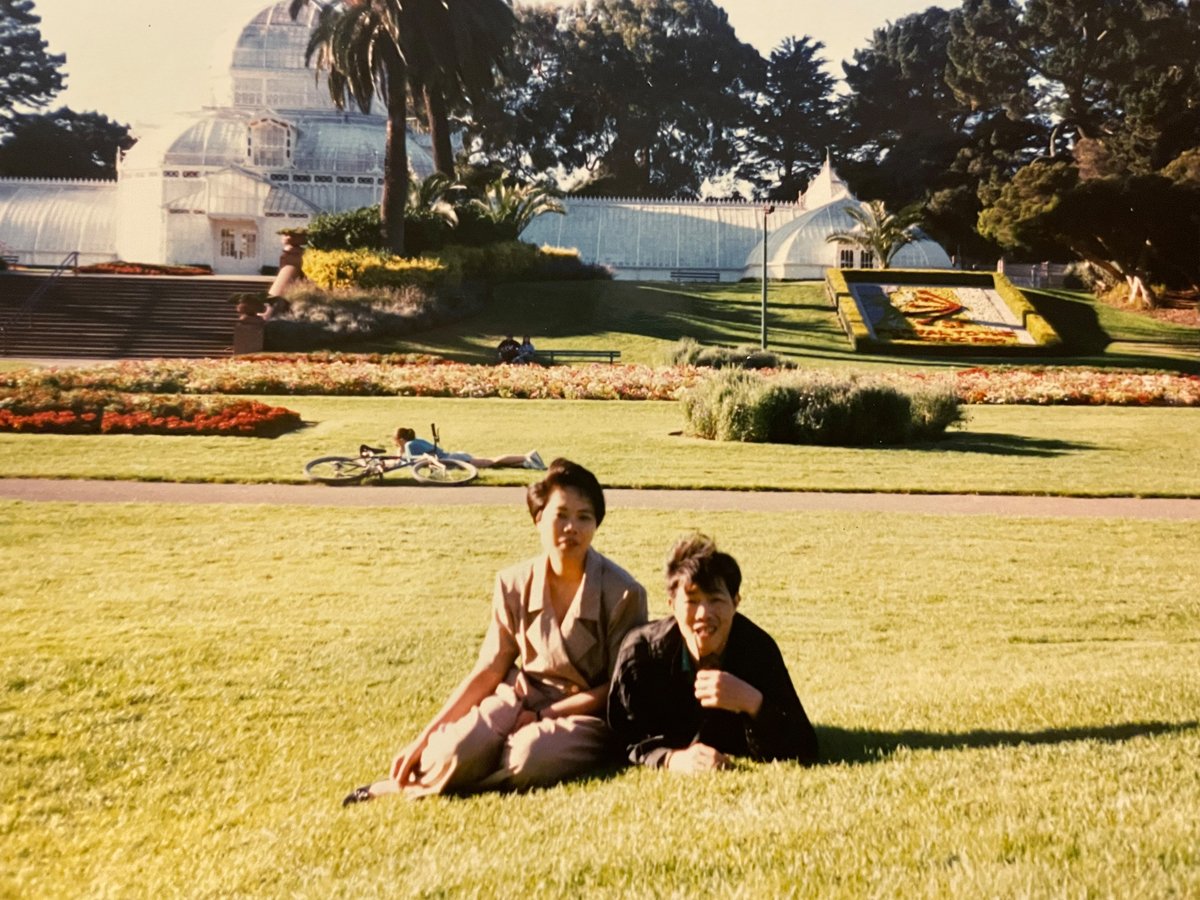

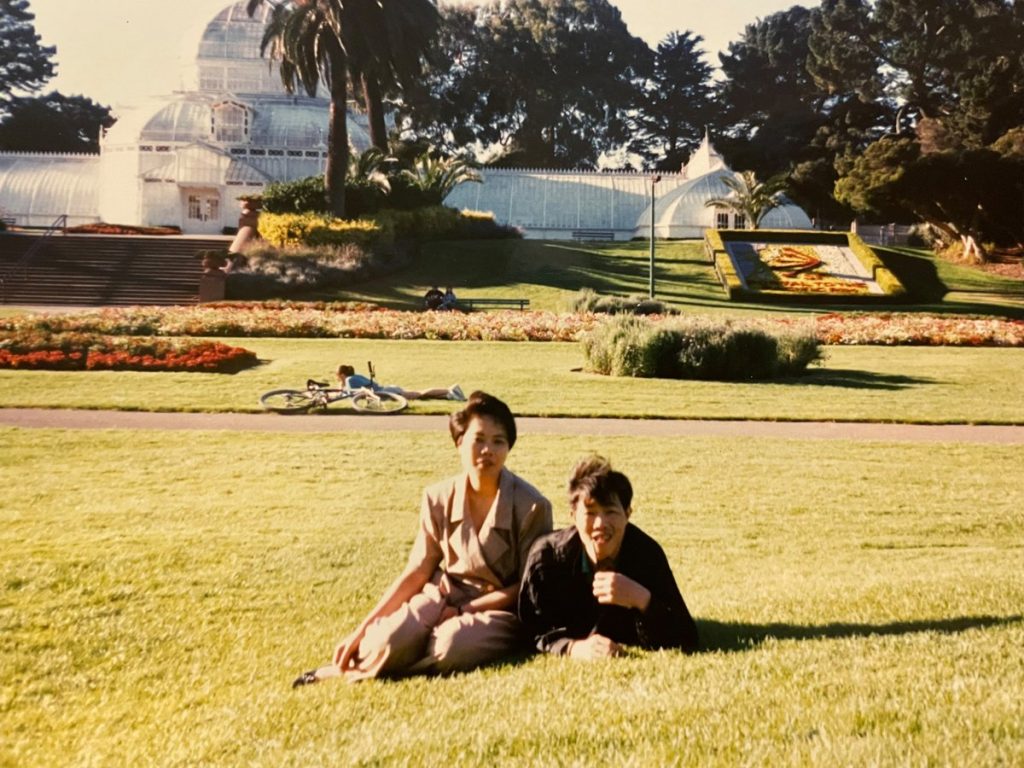

Senny Mau shows two sets of pictures. In one set we have snapshots that seem like brightly daylit dreams that came true, the kind of souvenir image that shows us having shown up at a famous place looming in the background. The other set is of low-light moody interiors with the soft focus of being half awake, half asleep. The first set seems like various moments in a long narrative. The second set seems like multiple views on the same moment. The first, making sense of a long journey; the second, making sense of a destination reached.

Laura Ming Wong gives us a set of pictures that in their size and graphics nearly jump off the walls. They are accompanied by audio, but without that dimension what we get is already powerful — gorgeously lit sitters in portraits which have the quality of each person assuming their favorite version of themselves, then, while in character, being interviewed close up.

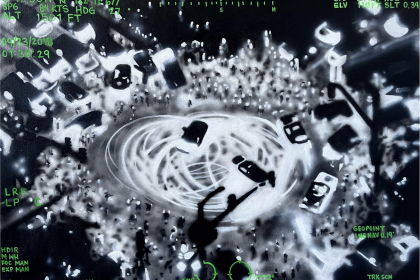

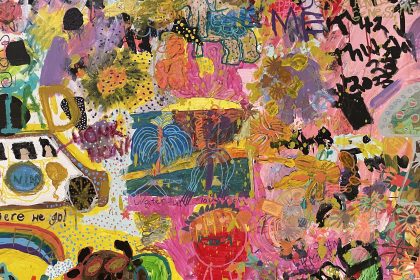

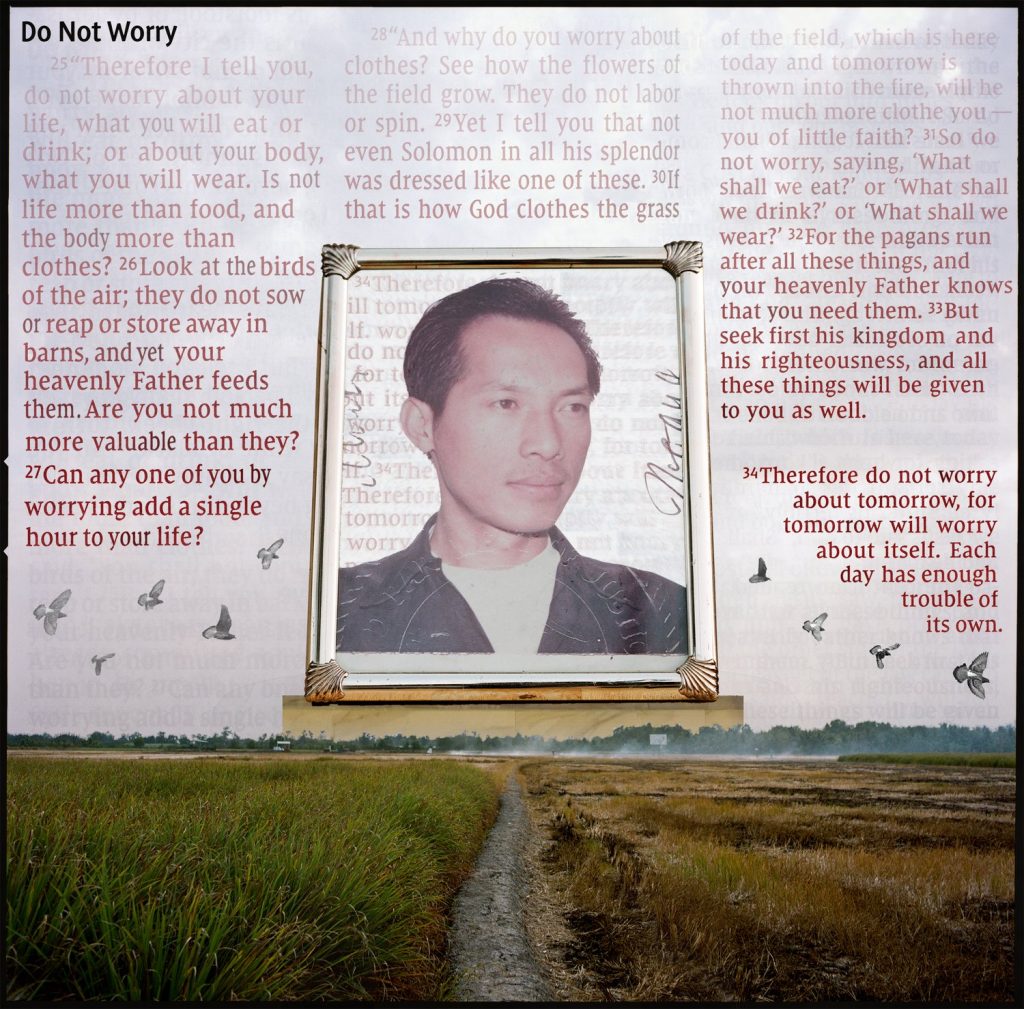

Matthew Hoang has the remaining set of pictures exhibited. They are an eclectic set of small, indestructible metal prints that, together, have a vivid energy of investigation, studying a few things again and again from different points of view. It is as if they are hunting for his father, trying to discover a version of him that has historical depth, but struggling with only a few clues. I say “as if” because Hoang’s texts, which (like the other artists’ did) tell a certain story explicitly, and we read how the images actually fit into it. But outside of that combination, Hoang’s picture group is the show’s most demonstrative effort-in-progress in creating a story – the effort that we would take on or continue when we leave the gallery.

____________________________________________________________

Malcolm Ryder, Oakland resident and artist, is a fine arts and commercial photographer and writer with 40 years experience in practice creating, teaching, and critiquing visual art as well as developing and managing arts organizations for visual artists. He is a graduate of Princeton University; a former programming developer and director at the NEA, NYSCA and NYFA; and former board member of arts non-profits in SF and Berkeley. His current art work, exhibiting in shows across the Bay Area since June 2022, is also published online at www.malcolmryder.com and at the home site of the multi-year collaborative art project Oaktown, at www.oaktown.pictures.

IMAGE CREDITS:

- Mom and Dad in the Botanical Gardens, San Francisco; Courtesy of Senny Mau

- When You Were Young, 1982 Bố at age 31 in Đà Lạt, Việt Nam; Courtesy of Ngân Vũ

- Lolo & Lola’s Picture on the Wall; Courtesy of Stella Kalaw

- William “Boon” Dominique; Courtesy of Gene Dominique

- Untitled; Courtesy of Najee Tobin

- Dad meets His Grandson. June 2022; Courtesy of Jessica Chen

- Mom and Dad in the Botanical Gardens, San Francisco; Courtesy of Senny Mau

- Terri Dora Wong; Courtesy of Laura Ming Wong

- Gospel; Courtesy of Matthew Hoang