By Malcolm Ryder

The most conceptual show I’ve seen recently is, appropriately enough, at a university. Mills College, which is now Northeastern University’s Oakland presence, opened its show of new works by three artists currently in its Art+Process+Ideas residency program.

The show announcement clearly states what we should expect: “approaches to artmaking that engage innovative uses of technology and performance to explore issues…”

I’ve omitted the list of specific issues that came with that description, for a couple of reasons.

First, I want to focus on the word “artmaking”, which accounts for the “Art+Process” part of the show’s title. I entered the show letting myself consider that this might refer either to processes that are informed by art, or to art that is done in the form of a process.

Second, I focus on the word “issues” and see that as accounting for the “Process+Ideas” part of the show title. I wanted to see the show with the question in mind of how ideas rely on being expressed through using a process, but also how a process is created from an idea.

The reason for taking that set of thoughts into the show was that I didn’t want the issues, as subject matter, to overwhelm the point of having artists address them. The literature advertising the show names immigration, personal and political power, and the environment as the issues, with their exploration being driven from a feminist perspective.

That’s high-intensity stuff; and depending on one’s own concerns, it could easily bring one to prioritize seeing this show above many others, without even emphasizing the technology and performance aspects that drive the innovation – the newness – of the art.

I’m not saying here that there is necessarily a “tyranny of the subject” at hand. Rather, if we believe that art is a special way of understanding the world and life, then an excellent outcome of seeing the show would be to discover that the works, in a way that we noticed, did enhance our understanding of the subject.

Again, this show derived from a university milieu, so it is fair to place more emphasis on how art does what it does; the show is actually, above all, about art itself.

Each of the three artists have a strategy of exploration, and the way their works function serves their strategy. [No spoilers are included here; nothing here substitutes for being with the works at the show.]

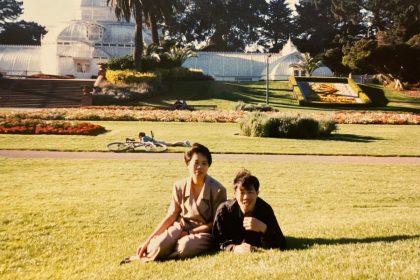

Heesoo Kwon takes existing imagery from the past, and using current technology including AI and 3D scanning, she intervenes in the images to change the limitations of what they could have shown. She adds to the prior images by digitally incorporating new images within them, and her additions are a critique of what came before. Her works consists mainly of new images made as photography and video.

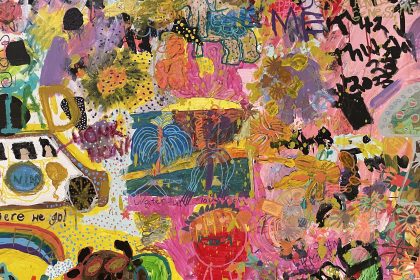

Ranu Mukherjee, in comparison, shows ways of finding meaning that are more corporeal; they rely on how our physical gesturing is an experience that communicates what we understand. Her works range from illustrations that examine gesture, to performances of gesturing, to instructions for gesturing. These are offered through paintings, video, and map-like dance floor diagrams that audiences are invited to try out. The floor piece allows the audience to directly examine how a gesture becomes something with a particular intended meaning.

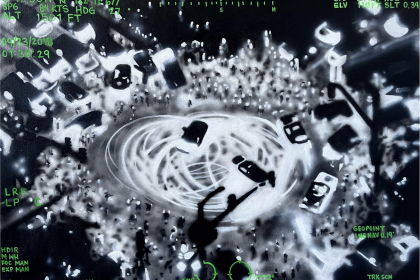

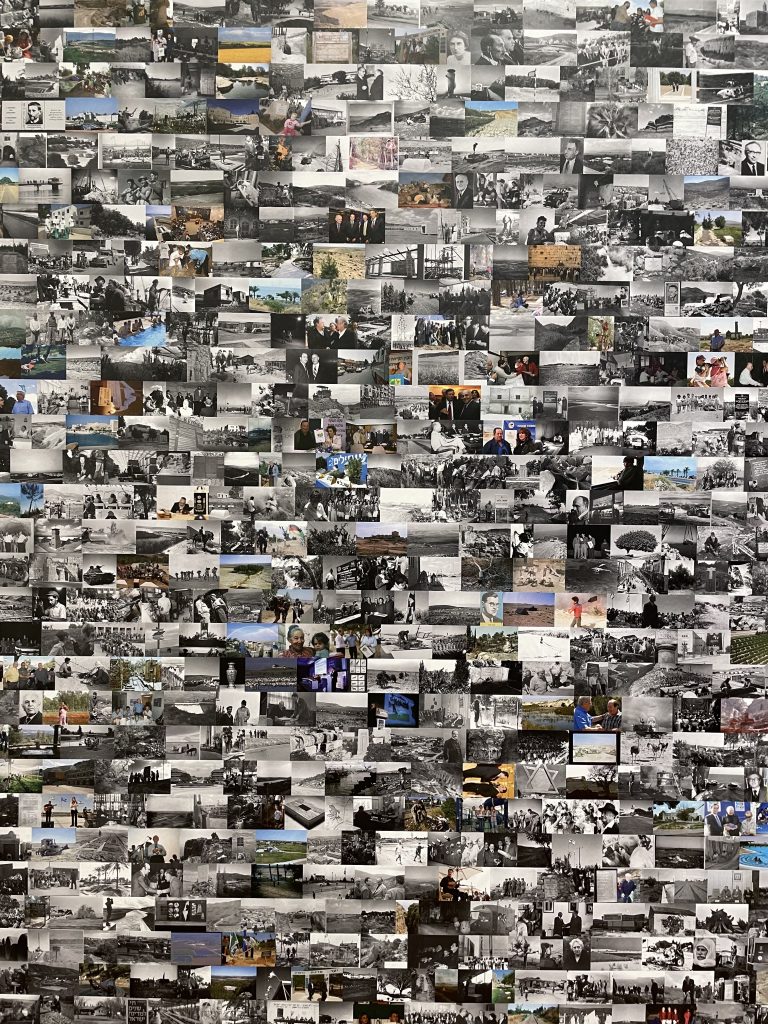

Liat Berdugo, like Kwon and Mukherjee, uses imagery from the past. But where Kwon intervenes and Mukherjee demonstrates, Berdugo’s strategy is forensic, in the way that a good investigative documentary usually is. Berdugo uses “hacker” technology to amass a staggering preponderance of circumstantial evidence about something, which is held in a secured archive. All of the obtained material is photographic; and the aggregation of it in the archive promotes certain ideas that Berdugo calls into question due to what she believes she knows differently today. Berdugo’s cloned image collection is formed into a gigantic wallpaper-like assemblage that argues the case for the very idea that she is now questioning. A selected portion of that is also in book form with text annotations that raise and develop her inquiry page by page. And finally, there is a dramatic video version of one particular narrative developed within the book. In comparison to each other, each of the three formats exposes what is missing from the other two, but at the same time exposes how each format tries to be distinctively convincing.

Leaving the show, I felt strongly that the title of the show could easily have been “History, Ritual, and Propaganda” instead of Art, Process, and Idea. Even further: the shared and overriding subject of the show is, I think, how Mythology works. My personal definition of a myth is “a description that has become a prescription”. In this show, the beliefs represented by past established imagery are not just accepted now but instead challenged for their current credibility.

The show, as intended, makes it apparent that artmaking can be a process for investigating ideas. In this case the ideas are of the myths, whether those myths be history, ritual or propaganda.

Largely rooted in personal histories, the works are provocative in that they pose to any viewer the question of whether what we think about ourselves is more symbolic than literal; more imaginary than real.

_______________________________________________________________

Malcolm Ryder, Oakland resident and artist, is a fine arts and commercial photographer and writer with 40 years experience in practice creating, teaching, and critiquing visual art as well as developing and managing arts organizations for visual artists. He is a graduate of Princeton University; a former programming developer and director at the NEA, NYSCA and NYFA; and former board member of arts non-profits in SF and Berkeley. His current art work, exhibiting in shows across the Bay Area since June 2022, is also published online at www.malcolmryder.com and at the home site of the multi-year collaborative art project Oaktown, at www.oaktown.pictures.

IMAGE CREDITS:

- Courtesy of Mills College Art Museum and Liat Berdugo

- Courtesy of Mills College Art Museum

- Courtesy of Mills College Art Museum and Heesoo Kwon

- Courtesy of Mills College Art Museum and Ranu Mukherjee

- Courtesy of Mills College Art Museum and Liat Berdugo