By Malcolm Ryder

At the Oakland Museum of California (OMCA), the art is a celebration of California. In OMCA’s current great hall exhibit Into the Brightness, the Bay area is the range, but the show’s focus is even tighter: the hundreds of artists who are members of Creativity Explored, Creative Growth, and NIAD. The exhibit showcases a dazzling array of art works having the common thread of being created by persons with developmental disabilities. That commonality, however, only intensified the impact of my first-impression entering the show – an explosion of abilities. Anything that can be shaped, colored, cut, bent, tied, glued, or written on seems to be in the show somewhere. And many of the works combine several of those moves in a single piece.

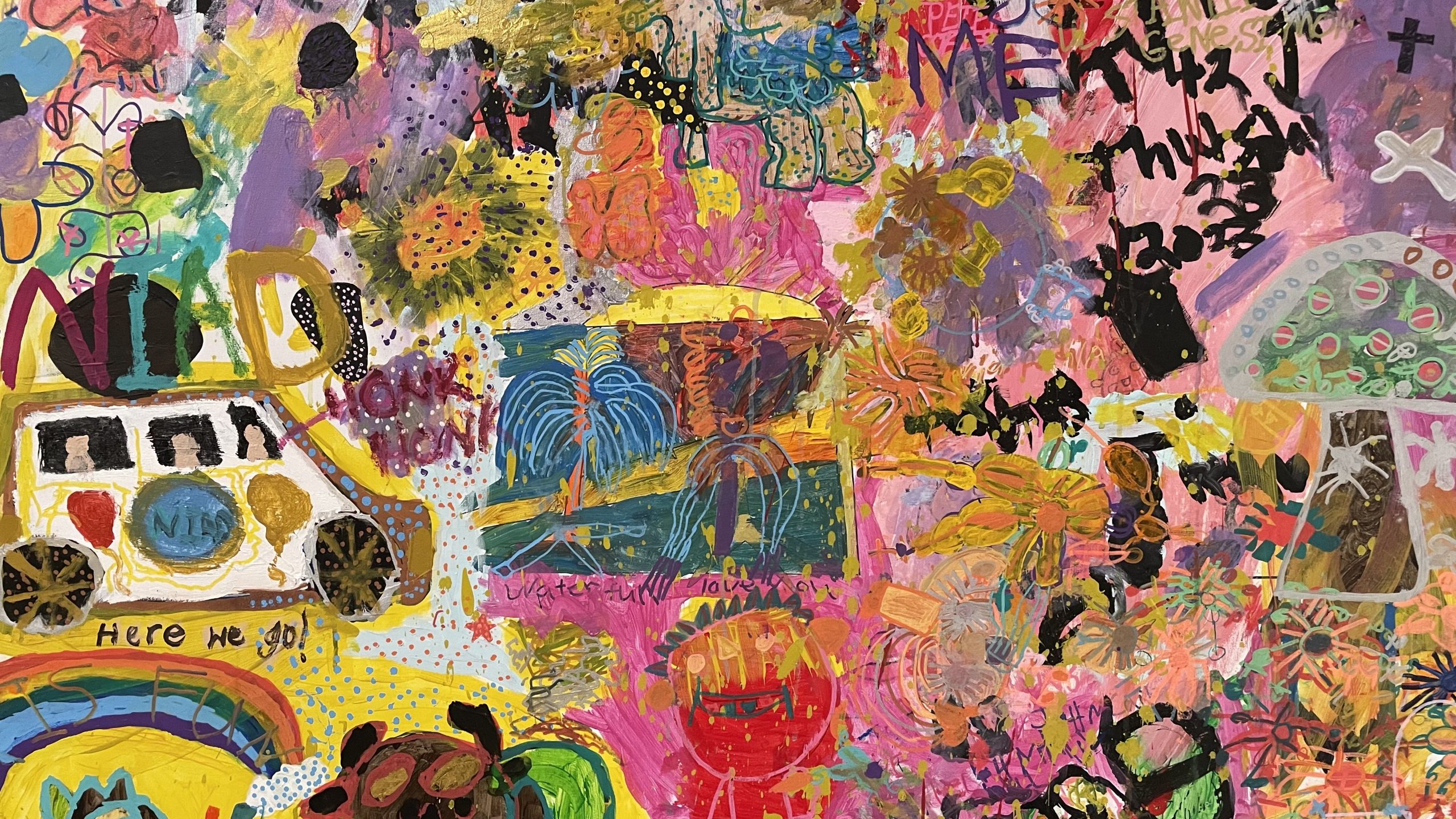

All three of the member organizations run like a cooperative. They all have the same founders and support the entire lifecycle of art production from inception to exhibit to sale and publishing. But as artist Pilar Olabarria said about Creativity Explored, it is “like a family, an extended art family.” Each organization clearly creates an environment, an incubator, in which a greater whole comes from the sum of its parts, while cultivating abundance and diversity of expressions. One of the first, and largest, pieces seen is a collaborative mural. The complexity and balance of the mural was an immediate demonstration of the “art family.”

Meanwhile, the various types of developmental disabilities here meant that each artist found personal “strategies” to translating their ideas and feelings into material form.

Said simply, the artwork emerges not from who they aren’t, but from who they are. Considering that the works have those things in common, conventional notions of artistic style, maturity, and strength of work are still relevant to the viewing experience here, but they are meaningful on a case-by-case basis. I felt that the achievement of each work could really be fully appreciated only with strong respect for that originality.

Yet much of this show’s work would be very comfortable in circumstances that are intentionally just as exclusive as this show is inclusive. We have this notion of “emerging artists” that is frankly about ones who begin gaining entry into increasingly restrictive criteria of critical or market value. But I have to say that the beauty of organizations like Creativity Explored, Creative Growth, and NIAD is their freedom from such external pressures on internally developing creativity and artistic achievement. The focus is on the emergence of the art.

The show’s artists have a range of subject matter that includes science, language, personal history, pop culture, news, nature, and comedy, as well as other “fine” artworks. And styles across the works give no sense of being prescribed to meet any pre-established ideas of value other than the artist’s own. Before leaving the show, I found it easy to embrace that every piece in it has the presence of a personal statement regardless of whether it seemed already familiar to me from elsewhere or not.

I think this aspect of originality is the most important thing to attend to about the works in the show.

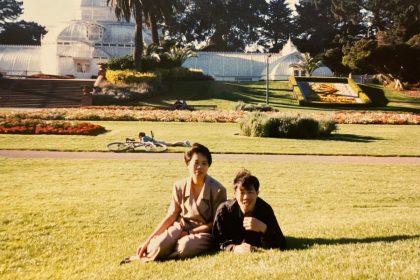

Marilyn Wong showed an exuberant painting that could be “read” as a portrait, a landscape, or a dream. But its composition is an energetically confident collection of painted textures that made layers or curtains with inviting spaces in between and behind.

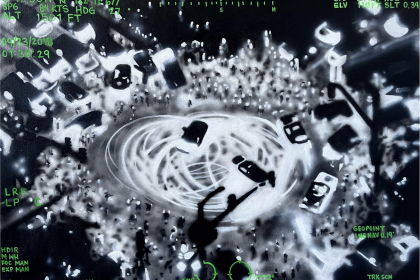

Monica Valentine, a blind artist, found a way to fuse color and form in a paradoxical work that asks us to touch it but warns against it.

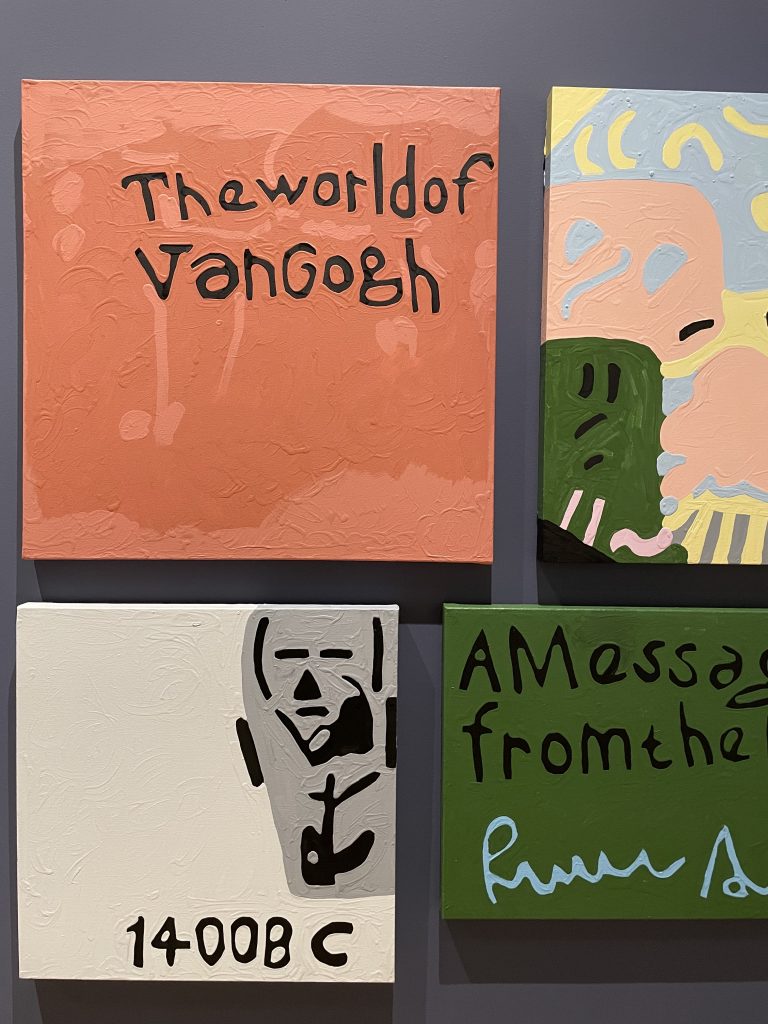

Karen May and others take their experiences of existing art products to shareable reinterpretation that questions and demonstrates how much we as viewers decide what an image is about.

But Jesus Huevo in The Kiss / Klimt shows that visual language, by any name, might be something rediscovered again and again because of how forms can somewhat naturally correspond to certain ideas.

And some artists worked in animation or video, which strictly speaking were multi-media works or that in some cases required us to work with them by becoming a part of their piece.

Coincidentally, as I left the show, I noticed that one of the two large exit tunnels takes us by the work of a very well-established independent artist, Jun Kaneko. He is quoted on that same matter of authenticity and expression: “Doing artwork is not work. It’s not hard for me. It’s like a necessity. It’s a heartbeat.” That’s a good preamble of the most important aspect of viewing the show: it is an “immersion experience” in making – that puts a lot of the art world into a refreshed perspective.

_____________________________________________________________

Malcolm Ryder, Oakland resident and artist, is a fine arts and commercial photographer and writer with 40 years experience in practice creating, teaching, and critiquing visual art as well as developing and managing arts organizations for visual artists. He is a graduate of Princeton University; a former programming developer and director at the NEA, NYSCA and NYFA; and former board member of arts non-profits in SF and Berkeley. His current art work, exhibiting in shows across the Bay Area since June 2022, is also published online at www.malcolmryder.com and at the home site of the multi-year collaborative art project Oaktown, at www.oaktown.pictures.

IMAGE CREDITS:

- Courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

- Courtesy of Oakland Museum of California

- Courtesy of Marilyn Wong and OCMA

- Courtesy of Jesus Huevo and OCMA