By Malcolm Ryder

Showtime

The Art of the African Diaspora, Richmond Art Center’s (RAC) annual exhibit for Bay area artists of African descent, is well into its third decade, having evolved from what had been the Colors of Black salon exhibit in 1989. Its current setup, which features RAC as a hub, offers well over 100 curated artists in exhibits distributed throughout more than 40 satellite galleries – many of which over the years have established themselves brightly enough to make their affiliation more of an outright constellation.

For the artists in this event, the front door to any of the shows is the entry criterion of where the artist came from. For the audience, attention turns immediately to where the artworks come from. And each additional year, the audience anticipates what will have changed or remained the same, having emerged from the curators’ latest attention.

The growing exhibit, marked by increasing success, enjoys extensive coverage in the community – which recurring stories say draws in significant numbers of newcomers through word of mouth, as well as attracting us all through widespread conventional advertising. For that reason, in describing my visit to the show, I’ll defer to its catalog and the abundant online sites that already give closeups of the artists and venues.

Instead, I’ll just probe some discoveries made about the artworks, from navigating the opening show at the Art Center itself. My notes here are complementary to the exhibition’s online gallery of artists at all locations. But these are thoughts intended for you to take with you to this show’s real on-land site, where the works on display have their proper impact.

The Artworks Inside the Show

Most of the pieces in the Art Center’s single large open show space is wall-mounted work, but includes a full range of 2D and 3D mediums. The wide variety of works at first seem mostly representational or figurative; and we spot a few photographs, but it’s hard not to notice the omission of other so-called high-tech or media items: film, video, and AI generated efforts. With the photography, the tension of its lingering techno vibe is remedied somewhat by considering how as prints it is more in keeping with the rest of the works. And photography’s small percentage of the exhibition no doubt reflects what the overall pool of pre-show submissions was like.

Meanwhile, the absence of mediaworks is a non-issue for this show’s audience, who specifically come to indulge in newer works within the exhibit’s traditional curatorial scope. And, on inspection, we can see within other genres numerous small distinct subgroups of one type or another.

While such groupings may become more apparent as we spend more time at the show, the installation keeps things well blended. But what assures the richness of each work’s difference, more compelling than its similarities, is the underlying complexity of how the works come to be.

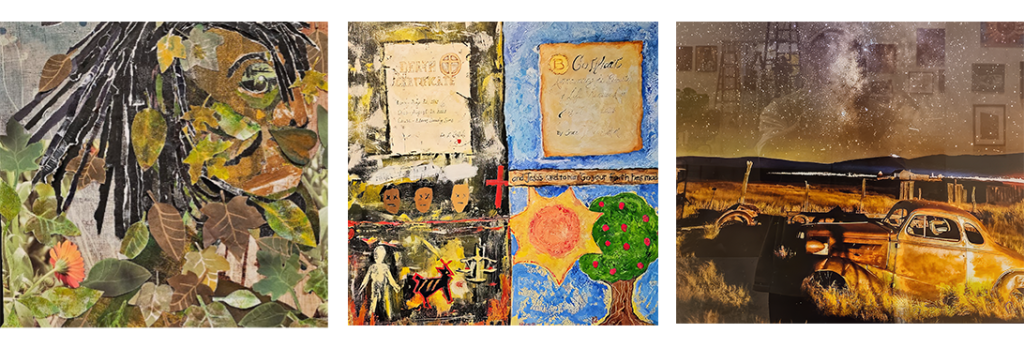

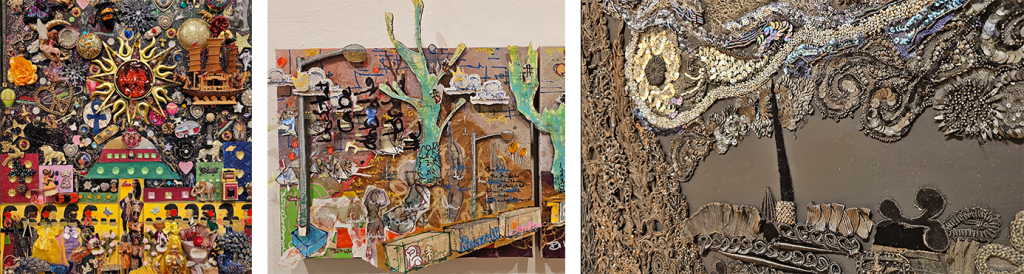

Diverse handlings of space by Valerie Brown-Troutt, Mychal, and Paula Vaughan

The Work inside the Art

For starters, individual artists of course have distinct motivations, current life circumstances, and familiarity on the scene. Likewise, key influences in their creativity come into play – cultural memory, social history, or personal sensitivity. From there, we expect that their work will somehow intentionally express those influences or derive itself from them. We might recognize that intention as a choice of artistic goals such as creating a feeling or idea or story.

Throughout the show’s set of works, those intentions range freely with no one of them monopolized by any medium or style.

In fact, in a way, the star of the show is Process more than Results. Most of the works are bold, showing emphasis on how the artist decided to handle the medium and the strength of expressiveness through craft is a clear characteristic throughout the show.

We often see physicality given special priority. There are objects in which imagery surfaces through high and low relief and others that are overtly assembled against the eye-level wall. Those pieces tie us viscerally to our awareness that we are sharing a space or environment with them, which makes us feel more like we are a part of the artist’s action. (Notably, that’s something that we expect with sculpture; the show’s more physical wall works and its free-standing sculptures or other objects associate with each other through this effect.)

Another effect of physicality is that we associate with some works because of the emotional connotations of materials – our long-term memory of using and living with them, and of identifying with them. Whether these associations are domestic, social or communal, they are signals reflecting our remembered selves, or our aspirational selves – and often, a desire to belong to a place or to each other. We might see personal items, dress, décor, or other representations of our world through an artwork using those materials.

Materiality in works by Paradise, Mark Heringer, and Cynthia Brannvall

In contrast, however, much of the other work successfully relies on a different strategy – using framing to mark off a more ceremonial or cerebral space, inside of which we have an experience either imaginatively or vicariously. Some of those works focus on bringing us to a person or place that already has special meaning to us. We see the artist’s commitment to making that subject vivid, and from that liveliness our place in the presented scene is felt.

Yet other pieces stand out because they confidently invent a persona or location. Among those works, a special characteristic is the way the artist assembles the whole from “parts”. The elements might be symbols, shapes, or items that individually have meaning but, as with the differing ingredients of a meal, they satisfy together through balancing their harmony and contrast. On balance, what is presented to us might be a type of place, or a character.

Characters in work by Simone Nia Rae, Akeemraheem, and Olubori Babaoye

The Individual Expressed

One could say that all of the variety mentioned above is about “style”. But I prefer to think of the artists’ diverse ways of getting to their goals as signatures.

As an artist evolves along with their body of work, the personal choices they make about why to express something a certain way can become as much the reason we come to see their work as is our preference in subject matter.

We may yet discover that the artists have differing ways of saying the same thing, and that can appeal to our connoisseurship of certain subjects or of artists. But in the best case, we also discover that a given artist’s “language” might be able to say something resonant that other languages cannot or had not before.

The Artists Gathered

As always, this exhibition wants to wrap its arms around all that it includes – without inhibiting the artists. Hovering over the show is the fascinating question of its dual nature: what shared African legacies underpin the works, and what uniqueness of the artist’s life presently pours into their artmaking? Taking te dual nature one step further, what binds the two things together in the artist’s consciousness, and is that binding the ultimate subject of the show?

That last question isn’t meant to be demanding or prescriptive; it is an invitation to explore. It makes our experience of the artworks more multi-dimensional, by sharpening our attention to any variety we encounter without debating the value of what we find.

Meanwhile, in the totality of the show’s works, we see inspiration flowing from the legacy, as well as innovation making new realities from that. This mirrors the diaspora’s path: bringing what one can of one’s own, to a new place of difference, where the need is to make that a place where one comes home.

As an analogy of the artist’s creative journey from motive to finished piece, “diaspora” tells us to look for who they are and how that identity is built into their finished work, which the curators strongly celebrate as “achievements”. And because the Center promotes the artists’ learning from each other’s efforts, their congregation from their individual paths creates community.

— Malcolm Ryder

________________________________________________________________

Malcolm Ryder is an Oakland-based photographer and Bay Area art critic, publishing frequently at Art About Town and Artdotdot.com. The designer and former manager of the Visual Artists Fellowships Grants process at the National Endowment for the Arts, he currently sits on the Boards of Oakland Art Murmur and the East Bay Photo Collective. His work is on exhibit at several satellite galleries in this year’s African Diaspora event.

All images above are excerpts of individual works by the respectively credited artists. Copyrights are reserved by the artists.