By Malcolm Ryder

Sometimes art gives a memory meaning, and sometimes memory gives art a meaning. In the current show at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center, curator Bushra Gill presents both cases, sometimes separately and sometimes blended, in a show that feels bigger and bigger the longer you explore it.

Gill’s show, which runs through July 27th, focuses on the idea that experiences which make up our sense of quality of life become permanent residents in our psyche and go with us to wherever else we call home. Over thirty artists are included, all of whom are present by way of their families’ immigration or having been refugees. The exhibit then shares with us those artists’ representations of their experiences.

Into the Mix

I entered the show during a vibrant street festival taking place in the plaza below the Cultural Center on 9th Street. But the sudden silence of entering the gallery immediately reminded me that the root of artist participation in this exhibit was about reflection. No less, the event is also specifically about Art. The exhibit looks to compare personal differences in the expression of its common theme: what makes memories persist. Each contributor’s work pursues some aesthetic that facilitates our grasp of why their memory has importance – or sometimes, questions it. So, the variety of its media won’t surprise anyone. It offers us painting, photography, collage and sculpture.

The show’s through-line subject is the continuing attachment to a place left behind. The imagery uses many strategies to represent what memorializes the attachment, literally creating what is meant by the excellent word “souvenir”. And finally, the collection conveys that memory can be evocative in a very straightforward way, but it can also be uncertain or complex.

There were too many items to cover it all in this one review of the show, but the below hopes to give more than enough reason to go explore all of it.

On the Walls

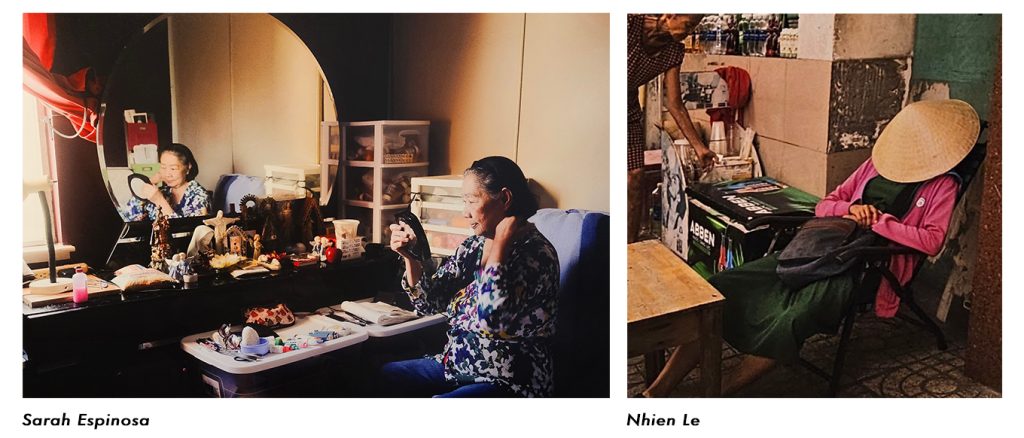

Two of the photographers lean on their medium’s authority as evidence of “typifying” scenes. In that way the moment in their images also takes on a sense of timelessness.

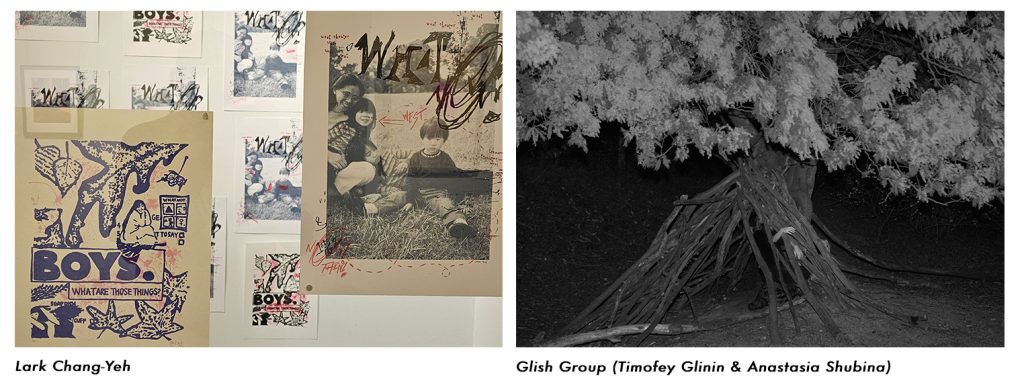

But two others go the opposite way, with works that question why we accept our ordinary images of things as being real or somehow settled, instead of being always open to interpretation.

One of the painters slyly comments on that idea as well, featuring miniature works that argue what we see and recognize is mostly subjective assemblage. Of course, that notion applies to the nature of the entire show itself.

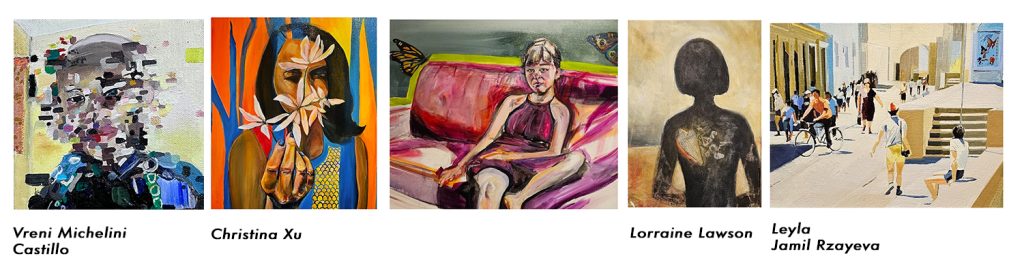

Four of the other painters, in widely different styles, offer moments of temporary isolation. But in each case the work suggests that these moments, all featuring a person in deliberate attentiveness, could be about either mystery or satisfaction. The works hover over the question of whether what we are looking at is the seeking or the solution.

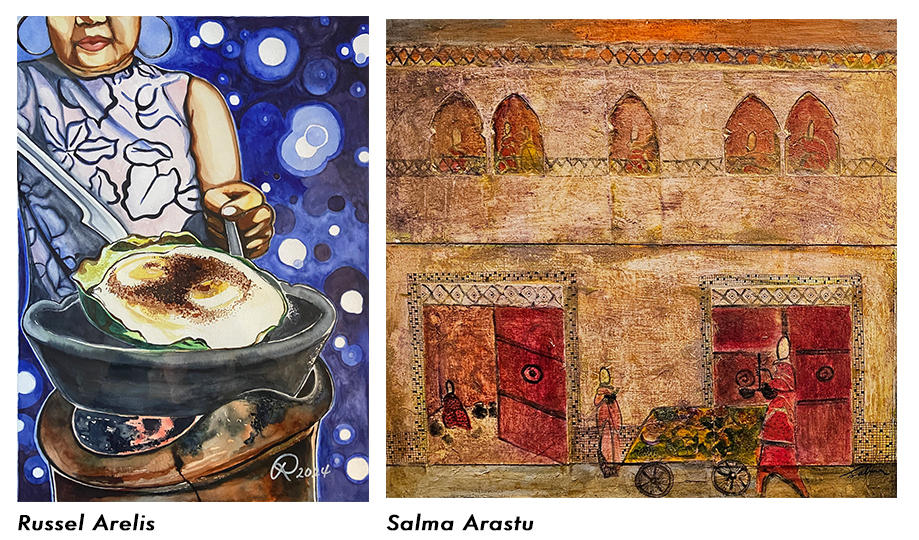

A different painter captures nuanced but deeply familiar moments of being cared for domestically. Ironically, these pieces have the almost dramatic quality of modern high-intensity graphic posters, while celebrating the undramatic intimate comfort of being fed. Meanwhile, as shown by a strikingly contrasting artist, domesticity is celebrated from a more distant point of view, with tableaux, done as if by historians cataloguing daily life, rendered in quiet tones like gilding patinas on ancient etchings with bright accents.

Two sculptural offerings emphasize the fragility of their singularly iconic forms like “house” or “gown”, exposing the vulnerable intricacy of details that compose them. They are metaphors for how our collection of individual moments and feelings is what turns their own impermanence into something larger and permanent yet always having the risk of decomposition. Does memory fade, or instead does it dissolve or crumble?

As if in answer, a collage artist recalls symbolic personal motifs and builds images with them in layers, regenerating joy or aspiration from those elements, and preserving their power to be meaningful.

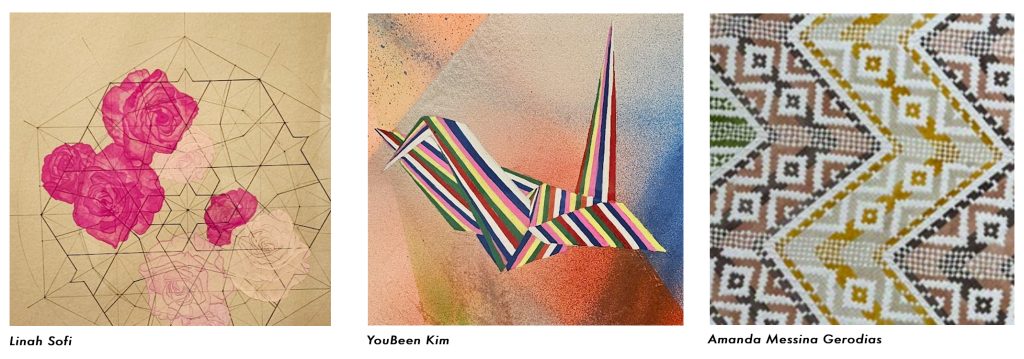

In other works that emphasize certain objects of personal desire, it is very overt visual patterns that have guided their formation and now the images of them. We see these items drawing their nostalgic staying power from their design. The way they are made is what fascinates us the most. And after all, design as craft, cultivated as a tradition, is one of the things most often taken as a distinction of a culture.

A Takeaway

In the scope of the full show, numerous other approaches including portraiture, abstraction and mixed media bring things or feelings (the show calls it “qualities”) that invoke the artists’ sense of places left behind.

But as the exhibit’s own written introduction suggests, the recollections may also indicate ways that the artists can connect to where they presently are. This could hardy be more appropriate to the mission of the show’s producer, the ArtTogether organization — to foster compassionate communities where refugees and immigrants can flourish.

Longing for Attachment, presented by ARTogether and curated by Bushra Gill, is on view through July 27 at the Oakland Asian Cultural Center.

Press Release | Artist Statements | Exhibition Page

________________________________________________________________

Malcolm Ryder, Oakland resident and artist, is a fine arts and commercial photographer and writer with 40 years experience in practice creating, teaching, and critiquing visual art as well as developing and managing arts organizations for visual artists. He is a graduate of Princeton University; a former programming developer and director at the NEA, NYSCA and NYFA; and former board member of arts non-profits in SF and Berkeley. His current art work, exhibiting in shows across the Bay Area since June 2022, is also published online at www.malcolmryder.com and at the home site of the multi-year collaborative art project Oaktown, at www.oaktown.pictures.